A new exhibit at the Plano African American Museum is shedding light on the often-overlooked role Texas played in the Underground Railroad, specifically through the network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom in Mexico.

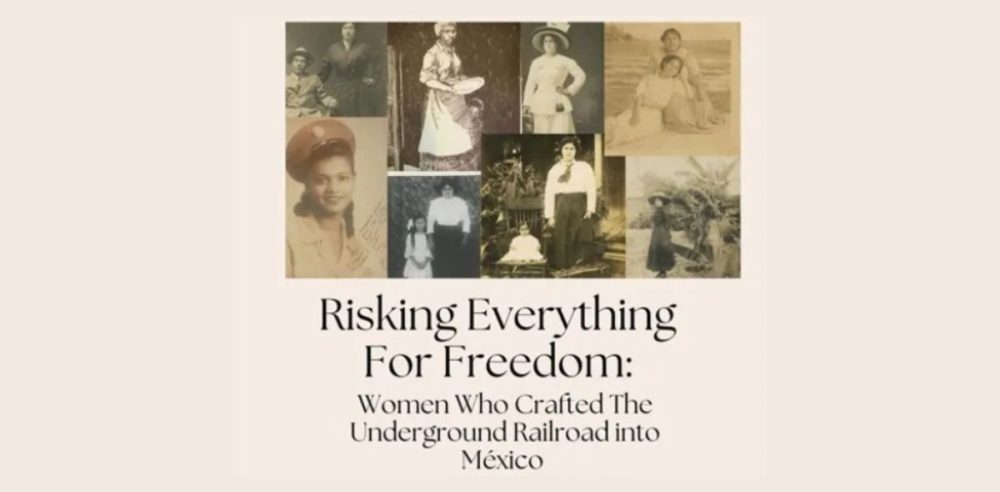

“Risking Everything for Freedom” is a tribute to the courageous women who forged the Underground Railroad from Texas to Mexico. Their inspiring stories illuminate the strength and resilience that fueled their relentless pursuit of liberty.

The exhibit, open to the public through May 3, is co-curated by the descendants of Silvia Hector Webber, who is affectionately remembered as the “Harriet Tubman of Texas.” Known for her role in organizing escapes to Mexico, Webber’s legacy comes alive through the powerful display of photos and documents that trace the journeys of those who risked it all for freedom.

While much of the focus in discussions around the Underground Railroad has centered on the northern routes, this exhibit emphasizes how enslaved Black people in Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alabama found a unique and often dangerous alternative route south — toward Mexico.

Webber’s family was persecuted as “Union sympathizers” and driven off their ranch; one of her sons was arrested, while another escaped to Brownsville, Texas. Silvia, her husband, and her children would then escape to Mexico themselves, returning in 1882, according to The Texas State Historical Association.

In the mid-1800s, Mexico had already abolished slavery, making it somewhat of a refuge for many seeking to escape slavery. Though historians have long recognized the Mexico escape route, details about the network organization have remained somewhat murky throughout history, as previously covered in a report by Axios.

The southern escape route to Mexico saw over 4,000 slaves, mostly men, fleeing to Mexico in the 1850s, according to Mekala Audain, assistant professor of history at TCNJ. Audain’s research found runaway ads, often the only records of enslaved people placed in Texas before the Civil War. The professor described how many escapees traveled 300-400 miles through the desert, often chased by slave catchers, on a much less organized and more “circuitous” route than the northern paths.

“There was definitely a biblical element to this wandering the desert and finding freedom,” Audain said.